Faculty Resources for Improving Digital Accessibility

Improving UCLA's digital accessibility is one of our main goals here at the DCP. With your collaboration, we can achieve more accessibility for students by building more accessible courses.

Here, we have some resources to help UCLA faculty build more accessible courses—namely, a two-part faculty quick guide for a crash-course on course accessibility, and multiple guides on more specific topics and scenarios.

Faculty Quick Guide: Universal Digital Practices

As the first part of our faculty quick guide set, this two-page guide gives a basic rundown of major digital accessibility practices and is a primer for understanding digital accessibility on multiple platforms.

To view this guide on our website, click the link in the heading above. We also have a PDF version of the Universal Digital Practices guide.

Faculty Quick Guide: Building an Accessible Course

As the second part of our faculty quick guide set, this two-page guide provides a guideline for building an accessible course—from what to include on your syllabus, to how to make various document types (such as Word or PDF) accessible, and more essentials.

To view this guide on our website, click the link in the heading above. We also have a PDF version of the Building an Accessible Course guide.

Additional Topics for Accessibility

Below, we have more resources for specific course scenarios or for diving in deeper on a given topic. We highly recommend you check out these guides, especially for any that pertain to your course materials in particular!

- Checking Color Contrast

-

Appropriate color contrast between a document’s text and background makes the content more accessible to people with different visual impairments. It also makes reading content easier for users without visual impairments.

To view the guide, follow this link: Checking Color Contrast

- Checking Reading Order

-

The reading order of a document or presentation determines the order that a screen reader will read out content. Verifying the reading order is imperative to ensuring that all students have equal access to the materials. Even if objects in your document or presentation appear to be ordered logically, you should always check the reading order.

To view the guide, follow this link: Checking Reading Order

- Choosing Accessible Course Tools

-

When building your course and selecting external educational tools (an online textbook, a code submission site, a polling service etc.), it’s important to choose products that ensure universal access for all students. This guide will help you find accessibility indicators and evaluate if a product or tool is likely inaccessible, or at least partially accessible. Once you find and evaluate a product or products, you can request consultation from the DCP to get expert input on the accessibility of your options.

To view the guide, follow this link: Choosing Accessible Course Tools

- Google Docs Accessibility

-

Microsoft Word and Powerpoint are best suited to make accessible, high-quality PDFs. That being said, if you aren’t planning on downloading and distributing your documents as docs or PDFs, Google Docs is an adequate platform. Here are a few things to keep in mind:

- Follow the universal practices - use alt text, descriptive hyperlinks, and appropriate colors and fonts.

- Note that Google Docs does not have the option to mark decorative images as such, so all images require alt text.

- Refer to the extensive Google Docs Accessibility Guidelines for more details.

- Graphs, Data Visualizations, and Infographics

-

For graphs/visuals, alt text can be longer than the typical 2-3 sentences. The detail of the alt text will be determined on the surrounding context, but a graph’s alt text will likely contain the following:

- Chart type (ex: scatterplot)

- x- and y-axis labels

- The general trend/pattern of the data

- Your reason for including the chart/what important takeaway it aims to display

For ensuring that graphs are colorblind-friendly, keep these things in mind:

- Avoid problematic color combinations such as red and green, green and brown, green and blue, blue and gray, blue and purple, green and gray, and green and black. These color combinations are problematic particularly for red/green colorblindness, which is the most common type. Thus, using these color combinations can render a chart or graphic entirely inaccessible to colorblind users.

- Use highly contrasted color combinations. Most colorblind people can detect contrast, so darkening and lightening your colors, respectively, make the difference more clear. You can do this with shades of the same color (i.e. light blue and dark blue), or with shades of different colors (i.e. dark purple and light yellow).

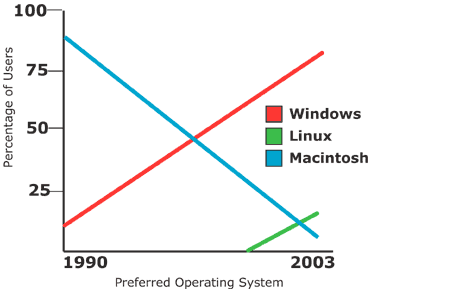

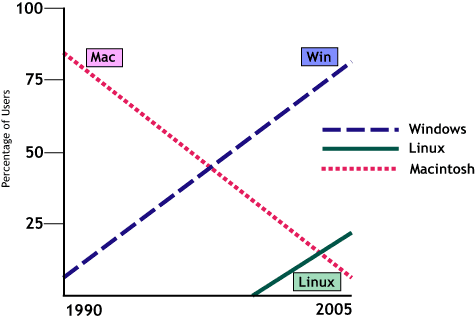

- Use patterns, textures, shapes, and labels in combination with color to effectively distinguish parts of a graph. See example below.

- For infographics, consider adding minimal symbols to further convey meaning.

- Keep designs minimal and streamlined.

Source: How to Use Color Blind Friendly Palettes to Make Your Charts Accessible

Example: using Color and Texture

The first graph below only uses color, whereas the second uses color, labels, and different line types (dotted, dashed, solid) to distinguish meaning.

(Example borrowed from Penn State’s Charts & Accessibility Page)

- Grouping Images

-

If you have multiple related images, it may be ideal to combine them into one larger, cohesive image. In that case, there's a bit of a special process to reinsert the grouping as an image so that screen-reader users can access the alt text and understand your content properly.

To view the guide, follow this link: Grouping Images

- Math Equations

-

Math equation accessibility is an extremely nuanced topic, but it is also extraordinarily important, as math is a major component of a myriad of UCLA courses.

To view the guide, follow this link: Math Equations

- Scanned Documents and OCR

-

The problem: Low-quality scans and PDFs without screen-reader-friendly text are prevalent in many UCLA courses.

Why it’s a problem: Low-quality scans are difficult to read, especially for students with visual impairments (and also for sighted students!). PDFs without any screen-reader-friendly text (or with inaccurate text) are not accessible for blind students and other students who utilize screen readers.

What to do about it: Assigned readings are a common component of UCLA courses. To make sure your readings are accessible:

- The best option is to find a digital, non-scanned PDF format of your desired document, or to evaluate whether this specific document is needed and cannot be substituted. If it is necessary, then we recommend trying to find a non-scanned version of your desired document before turning to scans.

- If you are using or making a scan, follow these two steps:

- Make sure that it is of a high quality. High quality scans should not include text that is cut off, crooked pages, dark shadows that create gutters, pages rotated 90 or 180 degrees, any sort of markings/underlinings, excessive italics, or blurring. (see below for examples of scan quality.)

- After securing a high-quality scan, use Adobe’s “Enhance Scans” tool on your PDF to make it accessible. For a quick 5-minute tutorial on using this function, follow along with our PDF Accessibility Part 2: OCR-ing a Scanned PDF video tutorial. (Note: “OCR” stands for Optical Character Recognition)

- You will know that the document is digitally readable if you are able to highlight text or do a word search in the document!

- Because OCR-ing a document may not always produce accurate text (especially with lower-quality scans), the MOST ideal option is a digital, non-scanned PDF version of the text.

Examples:

Example 1: Inaccessible - stray underlining and marks throughout the scan.

Example 2: Accessible! - text has no stray marks, is centered, legible, and clear. - Starting a Conversation About Disability

-

Encourage a personal relationship with your students! Express that you are open to listening to students who choose to disclose their disabilities. Know that syllabus disclaimers are NOT enough - make sure your students understand that you cannot initiate a conversation about disability, and encourage them to reach out to you early on via private means.

Creating a course environment where students feel comfortable coming to you to discuss accommodations, unexpected complications, etc. is a vital step to create learning environments where all students can thrive.

Here are some best practices for starting that conversation.

- Understand that disabilities are not always static.

- Understand that disabilities can be difficult to talk about (especially when they’re newly diagnosed), and sometimes students are afraid to ask for help.

- Don’t be afraid of saying the wrong thing.

- Don’t concern yourself too much with politically correct terms.

- Instead, ask what terminology someone prefers or what they are most comfortable with.

- Phrase things in terms of the student’s learning, rather than their ability or disability: “Would you like to discuss… (the upcoming test/assignment/etc)?”

- Universal Lecturing Techniques

-

Instructors should “consider the potential variation in individual skills, learning styles and preferences, age, gender, sexual orientation, culture, abilities, and disabilities as they select appropriate content and strategies for the delivery of instruction and then apply universal design to all course activities and resources” (Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction).

- Plan for accommodations.

- Know the CAE procedures for supporting students with disabilities, and review the section on Starting a Conversation About Disability (above).

- Provide clear statements of expectations for the course, individual assignments, deadlines, and assessment methods.

- Make your materials accessible and available before class.

- Employ interactive teaching techniques, and be sure to make interactions accessible to all participants, including those with disabilities.

- Describe content out loud whenever possible.

- Zoom Best Practices

-

- Make your materials accessible and available before class.

- Lecture in a quiet space, use a good microphone, and look at the camera.

- Discourage or minimize the use of chat if you know that a student is using a screen reader - chat is disruptive for screen reader users because when they turn on speech mode, it is read out loud over other talk and hinders them from following the meeting.

- Screen sharing and whiteboarding are inaccessible for students who are visually impaired or screen reader users. Describe content out loud whenever possible.

- For the deaf and hard of hearing, as well as English second language learners, consider enabling live captions in Zoom, making transcripts available, and using CCLE’s AI captions.

- Refer to the DCP’s UCLA Zoom Accessibility page for more extensive guidelines.

Faculty resources created by Annika Gillam ('21) Elizabeth Gallmeister ('22).